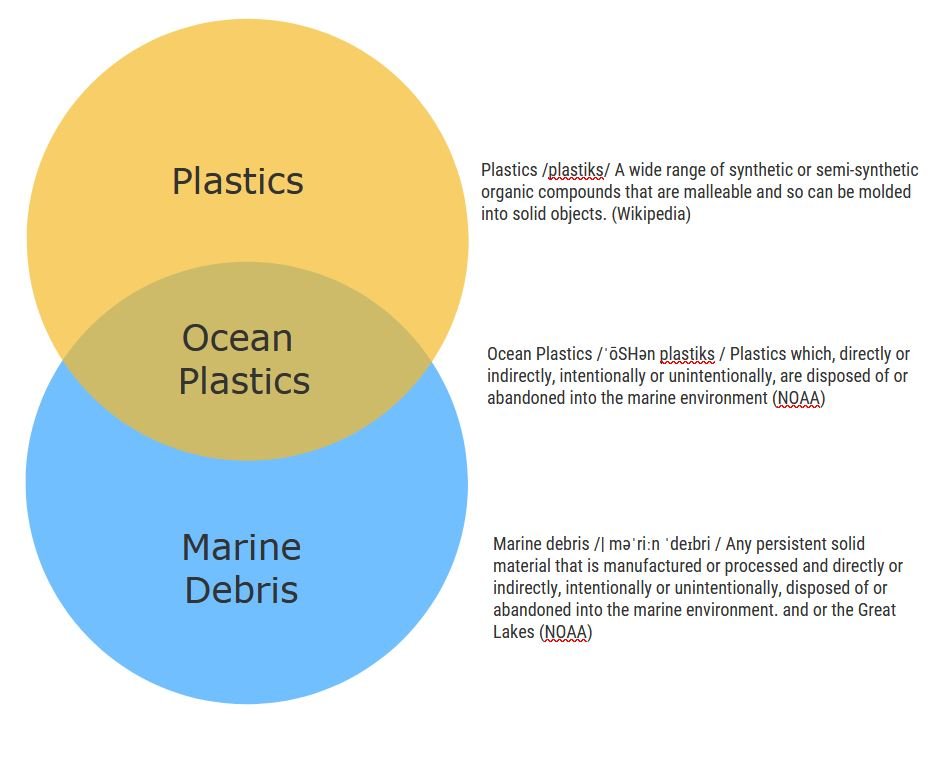

Ocean Plastics 101

Ocean Plastics are the Primary Component of Marine Debris

Most of the entangling nets and line that comprise the derelict fishing gear component of marine debris are made from artificial chemical compounds, otherwise known as plastics. For the purposes of the Ocean Plastics Recovery project, both soft and rigid materials are grouped under “ocean plastics.” Using this definition, ocean plastics comprise most of the marine debris circulating the oceans today.

They are Harmful to Fish and Wildlife

Ocean plastics have the potential to harm fish and other wildlife in two main ways.

Direct Impacts – Studies have shown that fish and other marine life eat plastic. Plastics could cause irritation or damage to the digestive system. If plastics are kept in the gut instead of passing through, the animal could feel full (of plastic not food) and this could lead to malnutrition or starvation.

Indirect Impacts – Plastic debris accumulates pollutants such as PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) up to 100,000 to 1,000,000 times the levels found in seawater. PCBs, which were mainly used as coolant fluids, were banned in the U.S. in 1979 and internationally in 2001. It is still unclear whether these pollutants can seep from plastic debris into the organisms that happen to eat the debris and very difficult to determine the exact source of these pollutants as they can come from sources other than plastic debris. More research is needed to help better understand these areas.

A “15-minute” sample of ocean plastics collected at Kalsin Bay, Kodiak Alaska in 2018. Plastics smaller than 5mm diameter are considered microplastics and are among the most difficult to remove from the marine environment. Island Trails Network photo.

They Never Really Go Away

Plastics will degrade into small pieces until you can’t see them anymore (so small you’d need a microscope or better!). But, do plastics fully go away? Full degradation into carbon dioxide, water, and inorganic molecules is called mineralization (Andrady 2003). Most commonly used plastics do not mineralize (or go away) in the ocean and instead break down into smaller and smaller pieces. We call these pieces “microplastics” if they are less than 5mm long. The rate of degradation depends on chemical composition, molecular weight, additives, environmental conditions, and other factors (Singh and Sharma 2008).

Bio-Based Plastics There are some bio-based (e.g., corn, wheat, tapioca, algae) plastics on the market and in development. Bio-based plastics use a renewable carbon source instead of traditional plastics that source carbon from fossil fuels. Bio-based plastics are the same in terms of polymer behavior and do not degrade any faster in the environment.

Biodegradable Plastics Biodegradable plastics are designed to break down in a compost pile or landfill where there are high temperatures and suitable microbes to assist degradation. However, these are generally not designed to degrade in the ocean at appreciable rates.

They Circulate all the World’s Oceans, but they Accumulate in Gyres

There are huge areas of the oceans where marine debris collects. They are formed by rotating ocean currents called “gyres.” You can think of them as big whirlpools that pull objects in. The gyres pull debris into one location, often the gyre’s center, forming “patches.”

There are five gyres in the ocean. One in the Indian Ocean, two in the Atlantic Ocean, and two in the Pacific Ocean. Garbage patches of varying sizes are located in each gyre.

The most famous of these patches is often called the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch.” It is located in the North Pacific Gyre (between Hawaii and California). “Patch” is a misleading nickname, causing many to believe that these are islands of trash. Instead, the debris is spread across the surface of the water and from the surface all the way to the ocean floor. The debris ranges in size, from large abandoned fishing nets to tiny microplastics, which are plastic pieces smaller than 5mm in size. This makes it possible to sail through some areas of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and see very little to no debris.

Andy Hughes photo

The Impact of Garbage Patches on the Environment

Garbage patches, especially the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, are far out in the middle of the ocean where people hardly ever go. Because they are so remote, it can be hard to study them. Scientists rarely get to see the impacts of garbage patches on animals first hand. So far, we know that marine debris found in garbage patches can impact wildlife in a number of ways:

Entanglement and ghost fishing: Marine life can be caught and injured, or potentially killed in certain types of debris. Lost fishing nets are especially dangerous. In fact they are often called “ghost” nets because they continue to fish even though they are no longer under the control of a fisher. Ghost nets can trap or wrap around animals, entangling them. Plastic debris with loops can also get hooked on wildlife – think packing straps, six-pack rings, handles of plastic bags, etc.

Ingestion: Animals may mistakenly eat plastic and other debris. We know that this can be harmful to the health of fish, seabirds, and other marine animals. These items can take up room in their stomachs, making the animals feel full and stopping them from eating real food.

Non-native species: Marine debris can transport species from one place to another. Algae, barnacles, crabs, or other species can attach themselves to debris and be transported across the ocean. If the species is invasive, and can settle and establish in a new environment, it can outcompete or overcrowd native species, disrupting the ecosystem.

Adapted from the website of the National Oceanographic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Marine Debris Program (marinedebris.noaa.gov)