The Role of +Nature in the Emerging Nature Market

Capt. Andy Schroeder of Ocean Plastics Recovery Project and Nina Butler, CEO of Stina, Inc. present to the UNWTO at Palma de Mallorca, Spain.

As the world continues its emergence from over two years of a global pandemic, we return to find that problems we were wrestling with at the close of 2019 – climate change, pollution and global inequality — are still here and getting worse. One by one, governments and decision makers are sounding the alarm, like this statement earlier this month by the UN Secretary-General after the launch of the third report of the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

“We are on a fast track to climate disaster: Major cities underwater. Unprecedented heatwaves. Terrifying storms. Widespread water shortages. The extinction of a million species of plants and animals. This is not fiction or exaggeration. It is what science tells us will result from our current energy policies.”

We know that as a material, plastic has contributed to this crisis. The oceans are filling up with it hundreds of times faster than it can be purged and microplastics have recently been found absorbed into our food, in our blood, in unborn babies’ placentas, and the air we breathe. There’s a lot we don’t know about the deleterious effects of plastics and chemicals inside human and animal bodies, but with some proven as endocrine disrupters and others killing untold wildlife through entanglement and ingestion, we know enough. We must stop polluting what sustains life on earth.

But it’s not stopping. By all accounts, it’s getting worse. It appears no amount of talk, and no singular or collective force is enough to bend our linear economy towards circularity.

This month we presented an idea we call +Nature (as in “nature positive”) to the World Plastic Summit in Monaco and to the UN World Tourism Organization at the Sustainable Destinations Summit in Palma de Mallorca, Spain. It was a call to action to establish a nature positive market to slow climate change by using offsets to restore the Earth’s capacity for carbon storage. There’s a lot to unpack here, but allow us to explain:

Source: US EPA

The analogy employed by the IPCC and others to describe the net warming effect of climate change is the “tap and the tub”. Although we have become hyper-focused turning off the “tap” of greenhouse gas emissions, we have been overlooking the ability of nature to “drain the tub” of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

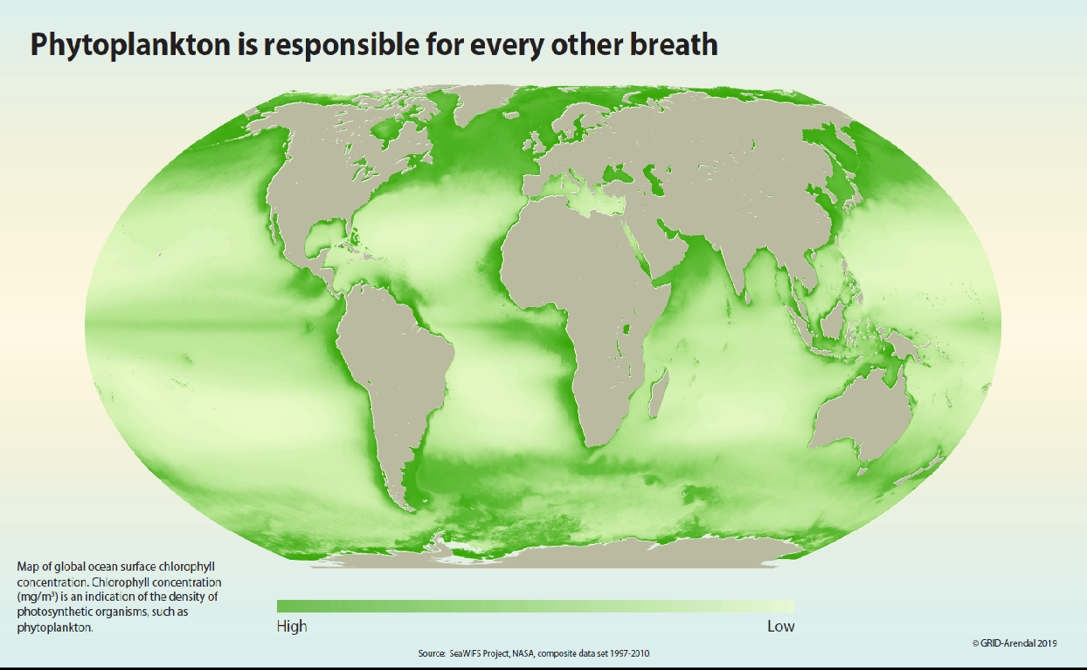

The most abundant greenhouse gas is carbon dioxide (CO2) and the only known method removing large quantities of it efficiently is through photosynthesis, which a fertile earth does naturally. In photosynthesis, the sun breaks CO2 into its basic elements, fixing carbon in plant and animal matter (nature) and releasing oxygen to the atmosphere for us to breathe. Forests, like the Chugach and Tongass forests in Alaska are obvious examples of photosynthesis-fueled carbon sinks. But in fact, most of the earth’s photosynthetic conversion takes place in the shallow “photic” layer of the ocean, where the sun penetrates certain nutrient-rich waters leading to phytoplankton blooms. Phytoplankton, it turns out, are responsible for 50% of the oxygen in the earth’s atmosphere.

When our planet is less fertile, when green lands turn charcoal black or slate grey, and when once-productive oceans become blue deserts, there is less photosynthesis in the biosphere. This is what’s happening now; through species depletion and habitat destruction, we have “clogged” the drain.

A recent study counted over 150 extinctions of megafaunal (44 kg or greater) species since we humans came on the scene, with South America having lost 99% of its megafauna. The same paper estimated that global nutrient transport due to animals has been reduced to about 6% of its former capacity.

As the largest of the megafauna, whales play a critical role in nutrient transport in the oceans. These highly migratory mammals feed from the depths of the ocean and defecate near the surface, thus contributing to both the horizontal and vertical transport of nutrients in the sea. The nutrient-rich water they help create lead to the phytoplankton blooms mentioned above, and thus we can thank the whales for performing an important environmental service.

We’ve never had to pay keystone species and ecosystems for the services they provide. But perhaps we should. In fact, the economic activity and wealth humans have created since the industrial revolution has been taken at the expense of the natural environment. Economists refer to this as externalizing our costs. Thanks to the work of economist Ralph Chami, we now understand that the services of the great whale can be valued in the carbon market, with each individual specimen over the course of its life providing services worth over $2M.

Image courtesy Stina, Inc.

Whales are the largest animals who ever lived and importantly, there are no known extinctions of these species. But after centuries of commercial whaling, ship strikes, pollution and overfishing, their numbers been reduced by as much as 90%. For those great whales whose lives are cut short, they are prevented from achieving their full potential, from performing these critical environmental services. This loss of biodiversity impairs the earth’s resilience. Their loss is our loss too, and as we try (and so far, fail) to develop ways to mimic nature’s ability to capture carbon, the continual decline of nature will have enormous economic costs and more importantly, jeopardize the ability of earth to sustain life.

This valuation of a whale may be the first step in a long-overdue shift toward natural capital accounting and the development of a nature market. The next steps are to protect the assets that remain by identifying the risks—to life, yes, but also a financial risk—to the asset. Then, we must mitigate those risks. This is where conservation and stewardship come in. If we can “make” more whales, either by reducing or eliminating sources of premature mortality, such as ocean plastic, or by furnishing the necessary ingredients for life (food, clean water, habitat) for them to live, then we can restore some of the wealth we lost and grow our economy by re-wilding the planet.

This transformation is not without pitfalls. Chami and his colleagues warn in a new white paper that “unchecked development of nature markets could lead to another historic round of nature-destructive and inequitable outcomes.” Indeed, carbon offsets themselves have recently come under increased scrutiny, with critics raising questions of additionality. Instead, they recommend establishing standards of governance and transparency to ensure this emerging market has a nature-positive and socially equitable outcome.

The beauty of this suggestion is that markets already exist for restoring nature--the voluntary carbon market. Driven in large part by the Paris Accords and COP26, the world is racing toward a carbon-based economy. Innovation will allow for the continued reduction of emissions, but demand for offsets will soon far exceed the available supply. The +Nature economic model points buyers of offsets in a new direction — toward enhancing the earth’s ability to sequester carbon by protecting keystone species, biodiversity and ecosystems.

This economic transformation is urgently needed. Rather than tell our leaders about it, we aim to show them, through a demonstration project by OPR in the United States this summer, soon followed by one abroad. These transactions will mark only the beginning of the nature market, for a valuation alone does not a market make. The valuation must spur economic activity. We hope by demonstrating the value of ocean plastic removal, we can amplify the efforts underway by others working to protect the services of nature, and that it spurs a dramatic shift in where we deploy our resources and human capital. There are many others working to unlock the power of the market to protect the natural world, but we will need even more of the best and brightest in the natural and social sciences to join us to ensure it is fair, just and transparent.